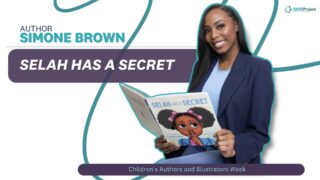

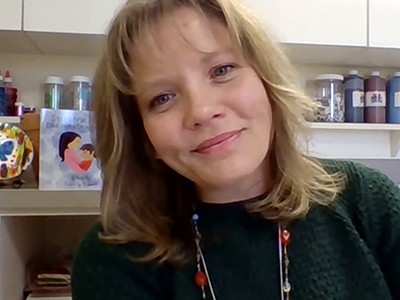

Children’s Authors and Illustrators Week 2023 continues throughout the entire month of February here at SAFE Project! Our second interview is with Melody Ray, author of Someone I Love Died from a Drug Overdose:

Melody was kind enough to sit down with SAFE Project to discuss Tommy’s story within the book, as well as share advice for parents on how to broach the subjects of overdose and death with young children.

Introduction and Tommy’s Story

Tell us a little bit about yourself.

My name is Melody Ray and I am the Healing Patch Coordinator at a children’s bereavement program in west central Pennsylvania.

Your book, Someone I Love Died from a Drug Overdose, actually opens with a quote from Fred Rogers: “Anything that is human is mentionable and anything that is mentioned can be manageable.” Can you share how that frames the story of Tommy, your main character?

The only way we can kind of really deal with situations is if we’re able to talk about them openly and freely, and by talking about these things, that can start the pathway to healing.

Tommy often mentions his feelings, but then is also asked to name and describe his feelings.

Yes. When he finds out that his dad died, there’s a whole swirl of emotions: confusion, not really understanding what’s happening, sadness, frustration, anger, and even embarrassment.

A significant part of the story is how hard it can be for a child to reconcile drug use and whether that is bad, and then whether the person who’s using drugs is bad.

In the book, Tommy’s experience as a young boy learning about drugs is from school. They talk about how drugs are bad, that drugs aren’t good for your body, and don’t do them. That was his whole experience as far as understanding drugs until he learns about the death of his father, which was from a substance use disorder. It’s that connection of, “I learned that this thing is bad, so that must make my dad a bad person.” And it’s really just that idea that we can make a choice, but that does not make us a bad person.

The story is about Tommy, but it’s also intended to be a workbook. How did that idea come about?

When working with the publisher, that was something we talked about that might be important: something for kids to do with their families, in a counseling session, or in a peer support model like the Healing Patch.

The back section also has kid-friendly definitions and explanations. How difficult is it to come up with ways to accurately, and even scientifically, describe some of these issues while still getting that compassion across?

I think a lot with kids it’s just frank, honest language. As adults, we’re used to euphemisms. We actually even avoid the word “death.” If you think about it, they’re gone, they went away, they passed away. Those can be really confusing for kids, so language that’s very straightforward and honest tends to be best when explaining difficult concepts.

How have you seen the book used, and what has the response been from families and children?

I think the biggest word is “validation.” People are parenting children and they’re questioning: “Do I tell them? What do I tell them?” There’s so much weight and such stigma around this type of death. It’s almost like a validation that it is okay to tell them, and the importance in starting with a basis of truth, and then continuing to share that narrative as the child gets older.

It’s a story, but there are also illustrations throughout the book. Can you share a little bit about the illustrations and the illustrator as well?

I went through a nonprofit publisher, the Centering Corporation, that picked up the book, and they found the illustrator. She’s a young artist in Florida, and just kind of getting her start, and she right away jumped on the idea of illustrating the book. What I had stated to the publisher was, a couple of images that were really important to me, were that image of Tommy with those feelings really swirling around him. I think just really understanding the multitude of emotions and feelings after giving such information, that it isn’t just one feeling, it’s a whole bunch.

Another illustration that really hits is the image of the brain with these ideas and feelings almost fighting inside, where one’s reaching out to this externalized pill bottle, and then you have another one holding it back.

Yeah, that was also discussed, with the idea of addiction being a disease of the brain. I always like the analogies with another very stigmatized death: suicide. We’ve gotten away from “committed suicide”; it’s now “they died by suicide.” You replace it in a statement like “they died of cancer” that “they died of a substance use disorder,” where you’re re-framing it in terms of it being a disease and a disease of the brain.

Within the story, the cat is a part of the family, and there is a striking two-page spread where the cat is kind of external looking on from afar.

So the image itself, that was 100% on the illustrator. Butterscotch is a real cat in my family that my mother-in-law owns that my daughter was really close to, and we just had that idea of the comfort that pets bring at these really difficult times for us.

Tell us a little more about the workbook. There are sections for writing, but there are also sections for drawing, illustrating, and even photos.

So developmentally, where the kids are, a lot of times they express themselves through the art. They may not have the ability to put their feelings in writing, but they certainly can with a sketch.

It really speaks to all ages, even though it’s simple illustrations and simple language; it seems like it can really reach all ages and stages of development.

My intention wasn’t that this happens in a family and they grab the book and they sit down and read this book. I think it was meant to be in terms of people parenting these kids in society as a whole of raising that awareness about how there’s a whole other layer to this epidemic, and there’s a whole lot of children that are being affected by this and they’re kind of like invisible grievers through this whole process.

There’s so much weight and such stigma around this type of death. It’s almost like a validation that it is okay to tell them, and the importance in starting with a basis of truth, and then continuing to share that narrative as the child gets older.”

Advice For Parents

One of the questions we hear so often is about when to start talking about this. Whether there is misuse in the house or simply seeing it in the media, when is too young or too old to start talking about this with children?

From our work in children’s bereavement, what we’ve learned is that as soon as a loss happens to death, one of the needs of the children is that they understand the physical reasons, like what made the person’s body stop working. I think as young as preschool, with language like, “they took too much of a substance and it made their body stop working.” Then that story is built upon as they get a little bit older, explaining the reasons behind addiction. Was there physical pain? Was there a mental health issue? And then just the idea that about addictive components in these substances and their effects.

This just came up the other night with a group that I was talking to where you say, “they took too much of a medicine.” Well, are they scared of medicine then? So it’s really clarifying that it’s only certain medicines that can be prescribed or drugs that do this. They’re clarifying that. For the caregivers, when they’re pulling things out of the cupboard, when they’re pulling a medicine for the child, that they’re now going to have to clarify some of that.

And that just goes the same as something like cancer. So they were sick with the disease called cancer, it made their body stop working, and they were at the hospital. So now anytime they think someone’s sick, they’re going to go to the hospital and they’re going to die, and they’re going to die of cancer. I think it’s just clarifying, keeping open dialogue, and that with that open dialogue, that narrative can continue to build. They don’t need every detail on day one. A lot of times they’ll let you know the amount of information that they need to know.

What we’ve learned in the children’s grief field is that when there are a lot of gaps or they’re not told, they find out anyway. Whether it’s an older sibling, whether it’s cousins, whether it’s on the school bus, they overhear the caregivers on the true cause of the death, and then it stigmatizes that much more and that makes that child grieve that much more all alone. My person died this way, and I can’t even be told how horrible of a thing that is? Then if they don’t and they find out many years later, there could be the natural thought of, “the adults were trying to protect me” and they can gain an understanding of that, but other times they feel like they need to re-grieve that person all over again. They’ve thought that they died one way and they’ve processed the grief and now they have to go back and revisit it all. We’ve learned that through the other stigmatized death, suicide, from over the years from children and families.

You really hit on the developing brain of children, with the cause and effect side of things, specifically with the phrase “stopped working.” That seems like a logical thing that even a developing child’s mind can understand.

In early preschool, there’s that magical thinking where everything is make believe. Cartoon characters die, but they jump back up. The whole idea of the permanency of death… they really don’t developmentally get that, and so there are repeated questions about it, and they’re very matter of fact in their language. A lot of times they’re at the grocery store saying, hey, my daddy died, my mom died, my grandma died. It’s them looking at reactions from the adults around them, and then every time they say that, it’s helping them with the reality of the death, and processing that developmentally. Then they start hitting, around 6 or 7 years old, to understand the permanency of the death, and they’re quite honestly focused on the cause of the death. What made that body stop working? What does that mean? And then they’re really trying to manage very unfamiliar and strong feelings that they’ve never had to experience.

There are some statistics that you wanted to share that might fit into the way that a parent or caregiver can read and use the book.

There’s something called the Childhood Bereavement Estimation Model that has been done by Judi’s House and the Jag Institute. They pull relative data from the CDC and they bring it to the forefront of children’s bereavement. I’m from the state of Pennsylvania and for the region that I live in, the drug induced death – so out of the percentage of all the deaths in 2019 – 26.6% in my region were due from a drug induced death, whereas the national average is 12.8%. That’s kind of putting in perspective where we were inundated with these calls. What prompted the book was, back in 2016, every other call for a brief period of months was due to a drug overdose from families. We would occasionally get calls for that type of death, but then it was like all at once, and it was really a lack of resources for kids on that topic, and really seeing that concentration here in our rural area of west central Pennsylvania for sure.

And it hasn’t gotten any better. Back when I had written the book, I remember using the stat, if this was in 2017, it was 72,000 or 73,000 Americans had died from an overdose. We compared that to the entire Vietnam War, and now here, we’re surpassing over 100,000 deaths in our country. The pandemic definitely exacerbated this, as well. What we’re seeing at our center is ongoing substance overdose calls on top of all other deaths, on top of COVID death. There are a lot of grieving children in our country right now.

How do we continue to support them throughout all of this? It seems like so much and, as you said, just piles upon itself with COVID on top of everything else.

I think number one is educating ourselves on just bringing them to the forefront that there is a ripple effect and that kids are being affected and that we look into programming that supports them. Across the country, there are many grief programs like the Healing Patch. There’s actually the National Alliance for Children’s Grief that people across the country can type in, and they can bring up any children’s bereavement program in their local area. Most of these programs are free, just like the Healing Patch. There’s no insurance. Basically, the families call after a loss to death, and they enroll and they connect with others. So it’s that power of a peer support model, as well as children’s camps. There’s a group called Eluna, and they have summer camps and meetings called Camp Mariposa, and that is directly a camp and mentor program for children that are dealing with a loved one’s substance use disorder. In this case, the person possibly hasn’t passed, or it can in fact be for children that have lost a loved one to an overdose. It combines both, but it brings them together through being with others. It kind of prevents that isolation, the normalization that, “I’m not the only one that is dealing with that.”

By bringing together the community, all of those types of things can be safeguards for the long run to help prevent the child themselves from engaging in high risk behavior like substance use.

Thank you to Melody Ray for advice for parents surrounding the topic of substance use and addiction. Someone I Love Died from a Drug Overdose is available on Amazon and via the publisher’s website.

Additional Resources

-

Page

PageJoin the No Shame Movement

Join our national movement to combat stigma, because there’s No Shame in getting help for mental health and addiction. -

Resource

ResourceLessons Learned: Talking to Young Children about a Loved One’s Substance Use

SAFE Project encourages families to start talking about substance use and mental health challenges with children at a young age. -

Page

PageSAFE Choices:

Serving Youth & Young AdultsPrioritizing the advancement of youth substance use prevention, intervention, treatment, and recovery.